How the United States helped spoil a plan to end gang violence in El Salvador.

Mayo 2019 / HARPER’S MAGAZINE

When I met Raúl Mijango, in a courtroom in San Salvador, he was in shackles, awaiting trial. He was paunchier than in the photos I’d seen of him, bloated from diabetes, and his previously salt-and-pepper goatee had turned fully white. The masked guard who was escorting him stood nearby, and national news cameras filmed us from afar. Despite facing the possibility of a long prison sentence, Mijango seemed relaxed, smiling easily as we spoke. “Bolívar, Fidel, Gandhi, and Mandela have also passed through this school,” he told me, “and I hope that some of what they learned during their years in prison we should learn as well.”

For the past eleven months, Mijango had been held in Sector 9, a VIP cellblock of the Mariona prison, for inmates who have “been involved in political things,” he said. He told me that he spent twenty-two hours a day with sixteen other men inside his cell, a space designed for four. There had been a news report that he attended yoga classes with former president Elías Antonio Saca, who was in prison on corruption charges. Mijango laughed when I asked about it. “No more yoga classes,” he said. “The instructor got hurt.”

Mijango, a former leftist guerrilla commander during El Salvador’s civil war, had been charged with conspiring with gang members to extort a food distribution company. He claimed that the charges against him were baseless and politically motivated. The government was targeting him, he said, because he had dared to take a new approach to the country’s problem of gang violence. In 2012, he negotiated a secret truce between El Salvador’s two largest gangs, MS-13 and Barrio 18, whose decades-long war had driven the country’s annual murder rate to rank among the world’s highest. Mijango’s truce cut the murder rate by more than half. It was the most dramatic reduction of gang violence El Salvador had ever experienced, and Mijango was invited by similarly afflicted neighboring countries, such as Honduras, to replicate the endeavor.

But now, seven years later, the truce is gone and buried, and the extortion charges are the latest of several indictments related to Mijango’s role as negotiator. Many Salvadorans have come to view him as a public enemy who helped strengthen gangs and attempted to enrich himself in the process. Others hail him as a hero who saved thousands of lives at great personal risk, and they blame the United States for sabotaging the truce and ruining the country’s best chance in years to curb gang violence.

For over twenty years, Mijango argues, the overwhelming influence of the United States on Salvadoran law enforcement has led to tremendous mistakes in security policy. Mijango believes that the United States pressured the Salvadoran attorney general’s office to prosecute him because it had opposed the negotiations from the beginning. “Condemning me has to do with the act of consummating that persecution,” he told me, “to not allow the possibility that in El Salvador, or in any other country, someone will think that that’s a way of solving the problem. It’s that simple.”

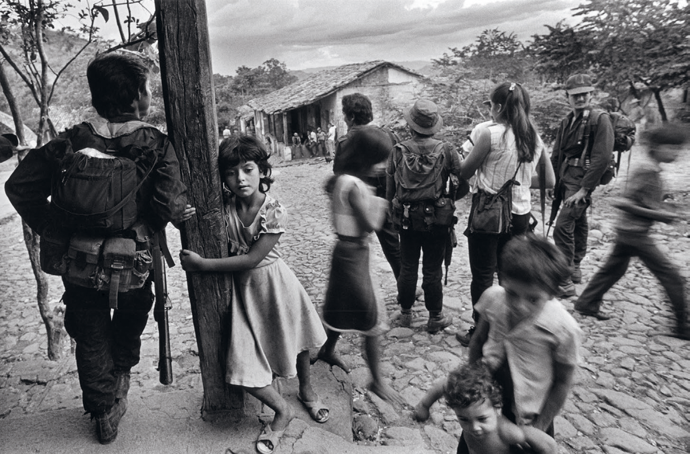

Before I came to see Mijango, I had not been back to El Salvador for seven years, since the beginning of the truce. My father is Salvadoran, and when I was a child we visited often, even during the civil war, a twelve-year conflict between the US-supported military government and the left-wing guerrillas of the FMLN. One excuse for my absence was that my closest cousins were now living in the United States, but—even as my family and I ranted on Facebook about Trump and the American media’s portrayals of El Salvador as a giant gang factory, a “shithole,” full of anonymous, tattooed, brown men staring out menacingly from behind bars—part of what had kept me away was fear. My father’s hometown, an idyllic place in my childhood, was relatively safe during the war, though sometimes we could hear mortars going off in the distance. When we passed soldiers on the road, creeping into the brush with their guns drawn, adults would assure me they were only “playing.” For a while, I thought a guerrilla was a kind of murderous ape. Swaths of the town are now split between Barrio 18 and MS-13. Members of my family have been threatened. Gangs even control the delivery of goods; my cousin told me that they really got on her nerves when they halted shipments of Coke after the delivery company refused to pay the extortion fee. Corpses have been found on the picturesque hill overlooking the town, the one we strolled up each morning during our visits.

San Salvador has become one of the most violent cities in the world. Despite the new malls, craft breweries, and recently renovated public spaces, the capital is a city of locked metal gates and private security guards toting shotguns on street corners. Seemingly every structure stands behind a wall of barbed wire. Much of the gang activity is concentrated in marginalized neighborhoods, but throughout the city a sense of risk can accompany the most basic activities, such as using public transportation or stopping at certain red lights. Above all, gangs manifest their power through extortion and territorial control, creating a geography of safe and unsafe spaces, a map of violence that shapes daily life. A common warning is allá asaltan: “They mug people there,” the third-person plural asaltan suggesting an invisible “they”—a faceless, sinister group, a uniform other. Nearly everyone I met had a story about being held up or threatened, even if, in true Salvadoran fashion, they often told it with a laugh.

For the past several years, since the collapse of Mijango’s truce, gang violence in El Salvador has been a leading cause of migration to the United States. Between October 2013 and July 2015, nearly eighty thousand unaccompanied minors from Central America were detained by US authorities along the Mexican border. According to a study by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 66 percent of Salvadoran minors interviewed at the border cited having been threatened or victimized by “organized, armed criminal actors” as a primary reason for fleeing the country. A 2017 report found that gangs are now responsible for 84 percent of forced displacement from El Salvador. In October, as a caravan of roughly five thousand Central American migrants, originating in Honduras, made its way toward the US border, a smaller caravan of Salvadorans followed, despite the US ambassador’s public pleas for them to stay put.

“I think if the US had been with us and given us a chance,” one of the negotiators told me, “there may have been less displaced Salvadorans showing up on their border.” The story of the truce and its dissolution is central to understanding the United States’ responsibility for the current migration crisis, and it suggests what it might take to comprehensively address the root problem of gang violence in El Salvador today. “We were convinced that after twenty years, the formula of repressive action to resolve the problem of violence wasn’t producing results,” Mijango told me. “We said, ‘We have to find another way here.’ And we found it.”

The war between MS-13 and Barrio 18 started in Los Angeles. MS-13, now the larger of the two gangs, was formed in the late Seventies, when Salvadorans who had fled to L.A. at the onset of the civil war banded together in the face of anti-immigrant discrimination from established black and Chicano gangs. They were young men who felt rejected by their new home. Barrio 18 is much older, an offshoot of Clanton 14th Street, one of the oldest Hispanic gangs in California. Members of Barrio 18 are known as los números, the numbers, while MS-13 are las letras, the letters. In both gangs, there is an emphasis on the power of words, palabras, and the value of verbal agreements. Leaders on the street are called palabreros. No one knows for sure how the feud between the two groups began, but it has killed tens of thousands and bred an obsessive mutual hatred that has become an integral part of the gangs’ identities. In one neighborhood in San Salvador, MS-13 allegedly banned DC shoes because the letters could be interpreted as shorthand for dieciocho, eighteen. At a Salvadoran prison in 1995, computer classes were abruptly suspended because veterans of Barrio 18 refused to touch computers whose operating system was MS-DOS.

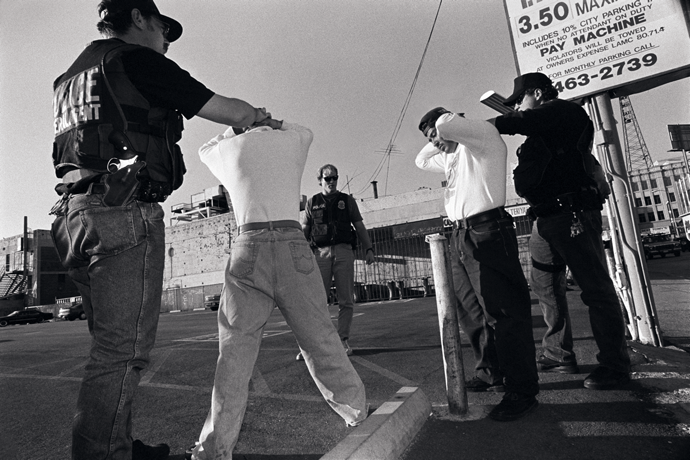

Many rightly blame the mass deportations of gang members from the United States in the mid-Nineties for the growth and radicalization of gangs in El Salvador, but Salvadoran policies were just as decisive. In 2003, ARENA, the right-wing party, implemented a repressive security strategy known as Mano Dura, or Iron Fist. At the time Mano Dura was introduced, the homicide rate was actually at its lowest level in years. But transforming gangs into national bogeymen proved politically successful, helping ARENA hold on to the presidency in the next election. Mass arrests were often carried out simply on the basis of appearance; wearing baggy clothes could be enough. And the United States supported Mano Dura vigorously. Roberto Castillo, a police inspector who was later involved in the truce, told me that law enforcement advisers from the American Embassy even gave arrest quotas to the Salvadoran police. “Lots of young men were captured and stuck in the holding cells, even though they weren’t gang members,” Castillo told me. “They became gang members there.”

Over time, gangs became more sophisticated, and more violent. The year 2009 was the most violent since the end of the civil war, with 4,369 homicides. The number of documented extortion cases also skyrocketed. That same year, the FMLN, the party of former guerrilla insurgents, captured the presidency for the first time, with a left-wing candidate, Mauricio Funes. Funes appointed David Munguía Payés, a former general for the military government, to be the new minister of public security, a post that would give him control of the state security apparatus, including the prison system. At the time, few appreciated that his appointment would reshape the gang war. The expectation was that Munguía Payés would double down on Mano Dura. But, in fact, he had accepted the post only on the condition that he be allowed to explore an alternative.

When Munguía Payés hired Mijango as an adviser, the ex-guerrilla was running a small business selling liquefied-gas tanks. The two men, former wartime adversaries, had struck up an unlikely friendship. Mijango had served as an FMLN congressman, but had since broken with the party over what he viewed as corruption and had abandoned politics altogether. Many of his fellow guerrilla commanders had been able to carve out successful lives for themselves after the war, but Mijango was broke. Like small businessmen throughout the country, he was forced to pay extortion fees to gangs, and he had learned to negotiate with them. “That was when I realized that they were people you could talk to and reach agreements with,” Mijango said in an interview with El Faro. He and Munguía Payés had often discussed employing the same approach at the state level. After the general’s appointment, they got their chance.

In February 2012, Munguía Payés sent Mijango to meet with the head of security at El Salvador’s maximum-security prison, Zacatecoluca, which lies behind massive barbed-wire walls about forty miles southeast of the capital, in the hot and humid Lempa River Valley. My grandfather, a former civil servant, was posted in the nearby town for several years, and his second wife had a catering business that provided food to the prison. That was before a gang rebellion, in 2014, turned the town into a battle zone—before the prison became known as “Zacatraz.” Today the prison houses more than six hundred of the country’s most dangerous criminals. The cement-block structure contains six floors. The lowest and darkest, Sector 6, is reserved for “The Heroes,” allegedly the oldest and worst offenders, who have access to a single window, about ten centimeters wide. The temperature inside often rises above one hundred degrees. The prison is home to the leaders of MS-13 and Barrio 18. In El Salvador, convicted gang members are usually grouped into designated prisons exclusive to each gang, but in Zacatecoluca, the bitter rivals are forced to coexist.

Mijango proposed to the head of security what seemed like a suicidal plan. With Munguía Payés’s support, he planned to bring the two gangs’ leaders into a single room—without shackles, guards, or cameras—to discuss a ceasefire. By the time he approached the head of security, he had been visiting the prison for weeks, meeting individually with gang leaders to explore the possibility of a truce. As if convincing the heads of MS-13 and Barrio 18 to negotiate were not enough of a challenge, Mijango also had to make sure the warring factions within the two gangs, particularly Barrio 18’s Revolucionarios and Sureños, were on board. “We talked to each group, to the MS, to the Mirada Locos 13, to the Revolucionarios, to the Sureños, to the Mao Mao, to La Maquina, to the ones they called the MD, and all the organizations related to the problem of violence,” Mijango told me. “We started talking to each one of them, in the sense of, ‘Look, you all are shitting on the country. We have to find a way to resolve this problem because in the end it affects you, too.’”

Mijango found that many gang members were in an existential crisis. They worried that their own children would join a gang and end up in prison like them. Some of them were part of the old guard, from Los Angeles, where gangs had played by a different, more restrained set of rules. While they accepted some of the blame, they wondered how they had become part of the rapid escalation of violence over the past decade. A few had already considered a dialogue with other gangs, but for the most part, the idea was taboo within their ranks, and possibly deadly.

Gang leaders were skeptical when Mijango told them that he’d been sent directly by President Funes to negotiate with them in order to lower the homicide rate. Politicians had tried to negotiate with them before, often in pursuit of votes from the communities they controlled. But soon the gangs found something to like about Mijango: he, too, had been an enemy of the state. There was a natural affinity between the ex-guerrilla, who had spent years trading blows with the military during the war, and gang members who had lived through Mano Dura. Borromeo Henríquez Solórzano, aka “El Diablito de Hollywood,” who had institutionalized MS-13’s extortion practices nationwide, was the gang’s leader and spokesman. “We like the fact that you’re the one who’s come,” he said, “because we know you’re not like any of those corrupt sons of bitches who came to see us before. That’s why we’re going to listen to you.”

Gang members were also willing to listen because they wanted something: better prison conditions. Adam Blackwell, a diplomat from the Organization of American States (OAS), a forum focused on regional cooperation, had recently presented a study of the country’s carceral system to security officials. The study found that Salvadoran prisons were overcrowded by 300 percent. “They had kids sitting in prisons with hardened criminals,” Blackwell told me. “It was a disaster.” Better conditions also meant more frequent family visits. Henríquez Solórzano, the leader of MS-13, had a specific request. Every year, for his birthday, his mother traveled from Los Angeles to see him, but they were always separated by a glass wall. What he wanted most was to be able to hug her.

The head of security at Zacatecoluca, a colonel, rejected the idea of a gang summit out of hand, but he soon got a call from Munguía Payés, who ordered him to allow the meeting to take place. The colonel agreed to step out of the way, but absolved himself of any responsibility if Mijango and his team didn’t make it out alive.

On the day the negotiation was set to take place, the atmosphere in the prison was especially tense. Due to a logistical error by security personnel, an MS-13 member had encountered a Barrio 18 member in a hallway, and the resulting fight ended only when the guards violently intervened. When Mijango arrived, a few minutes late for the meeting, the prison still smelled of tear gas. The colonel wanted to postpone. “You have no idea how bloodthirsty these people are,” he warned. “If they take you hostage, how am I going to rescue you?” Mijango, who was known for his bravery during the war—as the leader of the guerrillas’ special forces battalion, he was remembered for often laughing as the military closed in on them—was undeterred. Aware that Mijango had the full backing of the minister and the president’s blessing, the colonel could do nothing to stop him. He gathered over a hundred guards to stand ready outside the room in case of trouble.

As Mijango had stipulated, not a single guard was present as he sat down at the table. Roberto Castillo was there, as was Adam Blackwell, who had been sent by the OAS to broker the ceasefire, and a Catholic bishop named Fabio Colindres. The security cameras were blocked. Mijango had brought liters of soda; cigarettes; ice, which was a treasure behind the prison’s scorching cement walls; and boxes of fried chicken from Pollo Campero, the chain beloved by Salvadorans with a patriotic zeal. Shopping for the meal was what had made him late. “I’ve always thought that humanity’s best invention is the table, where everyone can sit in a condition of equality,” Mijango told me. “And if on that table you put a good plate of food, you can settle any difference.”

Yet it was hard to imagine a plate of fried chicken breaking a decades-long cycle of homicidal hatred. “A member of the MS could never be at a table with a Sureño,” Castillo said. “But apart from that, it was even more inconceivable that a Sureño would be together with a Revolucionario at the same table. And it was crazier to think that all three were going to be at a table.” Mijango hadn’t even told the gangs that their enemies would be attending the meeting.

Mijango sat at the center of the table, to separate the groups. The two factions of Barrio 18 came first. Among them was Carlos Mojica Lechuga, “El Viejo Lin,” the leader of the Sureños, a former guerrilla with a shaved head and a tattoo in cursive across his forehead that read, “En memoria de mi madre Rita.” They sat down on one side of the table without incident. But when the MS-13’s delegation entered the room and saw their rivals, they froze. Henríquez Solórzano, their leader, asked what was going on, and upbraided Mijango for not warning him beforehand. He said that it was too soon for the joint meeting.

“When is that moment going to come?” Mijango replied. “Who was going to determine it? We’re the ones who were going to determine that. And this is the moment. If you want to leave, then leave, but you’re not going to be able to share what we’ve brought.” Though visibly angry, Henríquez Solórzano sat down, his delegation whispering among themselves. “It was frightening,” Blackwell told me. “What I remember is just how terrified I was, because we were in this room with all of these guys, you know, no guards, no guns, no security, and I’m like, you know, who am I, the little white guy here.”

After the bishop led a prayer, Mijango urged the gangs to forget the fight that had occurred that morning and gave a speech about why they needed to stop killing each other and how it would benefit the country. When he finished, no one said a word. He waited for one of them to speak. He served the food, hoping it might help, but the gangs ate in total silence, stealing glances at one another.

One of the most valued items of the meal was ketchup. It was prohibited in Zacatecoluca because, the gang members explained later, the guards claimed it could be used it to manufacture explosives—a suggestion that made Mijango and Castillo laugh. Both had extensive experience making explosives during the war. According to El Faro, an MS-13 member saw that the ketchup and other sauces were on Barrio 18’s side of the table and asked for someone to pass them down. A Barrio 18 member complied, and the sauces were passed back and forth. The gangs remained otherwise silent, until Henríquez Solórzano, apparently sick of the tension, finally stood up. He walked around the table, in Mijango’s direction, and then past him. With everyone watching, he came to where Mojica Lechuga, the Sureños leader, was seated. Mojica Lechuga stood up. Henríquez Solórzano extended his hand, and Mojica Lechuga shook it. Then they began speaking in English. Both had become gang members in Los Angeles. “Please, in Spanish,” Mijango told them. “Not everyone here speaks English.” “I was just telling him,” Henríquez Solórzano replied, “that this is the historic opportunity we’ve all been waiting for.”

Less than a month after the meeting, Mijango helped bring the gangs to an agreement, which stipulated that they would cease hostilities between them, as well as toward law enforcement and civilians, and participate in a process of dialogue. In exchange, they would receive better prison conditions, the abolition of harsh anti-gang laws, and the cessation of police and military activity in gang territory. Everyone agreed to keep the accord a secret. Mijango and Munguía Payés knew there would be an outcry if the public found out about the negotiations before they could point to concrete results, and the gangs needed time to get the clicas on the street in line. Thirty gang leaders, accompanied by Mijango, were allowed to leave the prison in buses provided by the government, to meet with clicas and reestablish their control.

After this meeting, the leaders were transferred permanently out of Zacatecoluca to lower-security prisons where they would have access to phones and could continue coordinating with the clicas on the outside. But a few days later, El Faro released a bombshell report that detailed the agreement. The revelation that the government had held clandestine talks with convicted gang members and had granted them unusual benefits was a stain that would forever mar the truce in the eyes of a population traumatized by violence and corruption. It exposed what would be two of the ceasefire’s most debilitating flaws: zero transparency and a total lack of a communications strategy.

For the negotiators, the report was a disaster, and the accord suddenly appeared untenable. But then the number of murders started to fall. The month before the transfers, there had been an average of 13.6 homicides a day; afterward, that number fell to single digits. “We caused, in forty-eight hours, a reduction in the situation of violence in the country that hadn’t been accomplished in seventeen years,” Mijango told me.

These results soon quieted the truce’s harshest critics, and the agreement eventually garnered bipartisan political support—unheard of in El Salvador. The murder rate dropped from 70 per 100,000 in 2011 to 41 per 100,000 in 2012. Mijango convinced the gangs to surrender weapons in public ceremonies as a gesture of good faith. Among the weapons they relinquished were M16s and a Claymore mine, supplied to the Salvadoran military by the United States during the war. The first ceremony, in Ilopango, a municipality just outside the capital, was a grand spectacle in the main plaza. The mayor spoke, as did Munguía Payés, who by then had admitted the government’s role. They were followed by representatives of both gangs. The simple act of gang members gathering en masse and showing their faces had a powerful effect.

“The people didn’t know what the hell was going to happen,” Paolo Luers, a journalist and former guerrilla press officer who became part of Mijango’s team, told me. Music was playing and a platform had been set up in the plaza. Suddenly, a column of MS-13 members approached, followed by Barrio 18, and soon the plaza held about two hundred gang members. “Before, they had killed each other, and they never let themselves be seen like that,” Luers said. Spectators were astonished that there were so many gang members in their community. “This utopia is possible,” Mijango said in more than one interview.

Mijango was sought out even for matters unrelated to the truce. Families turned to him when their sons went missing. The line between mediator and gang representative became increasingly vague, and in one crucial case, legally murky. In 2012, Mijango mediated a negotiation between Arrocera San Francisco, a food distribution company, and the gangs who were extorting it. He convinced the gangs to lower the monthly extortion fee from $15,000 to $6,000, and to modify the form of payment from cash to goods, such as rice, beans, diapers, and cooking oil, so that gang members could sell the products at stores that would employ their families. Although the company ultimately benefited—the owner sent gang members Christmas baskets and turkeys in gratitude—prosecutors would later accuse Mijango of being an accomplice to extortion. According to Blackwell, these negotiations were part of efforts to increase support for the truce in its next phase, especially among the business community, which had been heavily opposed at first. But there was no clear strategy or order from Mijango’s superiors to proceed in this way. “His passion to find solutions . . . may have gotten the better of him,” Blackwell told me.

Throughout the process, Mijango viewed the Americans, not the gangs, as his principal antagonist. He knew that without the support of the United States, which funds Salvadoran law enforcement, the truce would be unsustainable. Mijango told me that US security officials initially reacted to the talks with anger, claiming that they interfered with intelligence operations. Gang informants, after years of getting nothing in return for their cooperation with the FBI, had stopped talking to the Americans, and saw the truce as a better option for improving their conditions. But negotiators continued to lobby the Americans, even traveling to Washington to meet with diplomats and security officials.

Nevertheless, in October 2012, about eight months into the truce, the US Treasury Department designated MS-13 a “transnational criminal organization.” MS-13 is larger than Barrio 18 and has a more widespread presence in the United States, but many have argued that the gang’s reach and finances are not even close to those of other groups on that list, such as the Japanese Yakuza. It was a move intended to make it more difficult for the gang to transfer money from the United States to El Salvador, but it also made it illegal for US federal agencies to financially support social programs that engaged directly with members of the gang, as some of Mijango’s community initiatives did. “The gringos drew a line,” said Luers, who was in close contact with the Americans. “They said, ‘Not one dollar for programs that work with gangs directly.’”

According to Mijango and Luers, there was a difference of opinion between US diplomats, who were in favor of the truce, and US law enforcement officials, who were opposed. The Salvadoran government itself was torn. President Funes’s public stance on the negotiations remained ambiguous. Abroad, Funes promoted the drop in homicides, but in El Salvador, he continued to present the truce as an accord strictly between gangs, with the state involved merely as a facilitator. What this meant for Mijango and the other negotiators, in practical terms, was that they were for the most part on their own. Many police officers, veterans of Mano Dura, had no confidence in the process, and in some cases even tried to disrupt it. Castillo, one of the few officers involved, recalled having to evade fellow police officers when he went into neighborhoods to pick up weapons that the gangs surrendered.

Mijango became the public face of the truce, a role that Blackwell says was a bad fit. In televised interviews, he was often put on the defensive. Sporting a neatly trimmed goatee and a white guayabera (an emblem of peace throughout Latin America), he would call on the government and the public for more robust support, and in his gravelly smoker’s voice, sympathize with the gang members. “They find something in the gangs that fills that void that society and family haven’t been able to fill,” he told El País. When asked about a particular homicide, he sometimes sounded like a Mafia consigliere, complaining about rebellious clicas and promising that gang leaders would fix the problem—obviously through violent means. In a call that later became public, he urged Henríquez Solórzano, the MS-13 leader, to punish a gang member who had killed someone. “You all know what to do,” Mijango told him.

By the end of June 2013, Mijango’s utopia began to show cracks, as powerful critics of the truce emerged. Luis Martínez, the attorney general, who had strong ties to ARENA and a close relationship with the American Embassy, called the process “hypocritical” and Mijango “a buffoon and a liar.” Martínez falsely claimed that gangs were becoming better armed and more violent. Media outlets spread false reports that gangs were killing just as much as before, but burying their victims in clandestine cemeteries. The cemeteries did exist, but they had been around for years, and most of the bodies exhumed were found to have been buried before the truce. Mijango was circumspect in his rebuttals but claimed the attacks were a political ploy by the right, because continuing to support the truce would mean “recognizing the success of this leftist administration, and their own failure.”

For the most part, politicians in both parties had remained supportive, citing the decrease in homicides. That changed as the 2014 presidential election approached. ARENA’s presidential candidate, Norman Quijano, condemned the truce. “The government comes to an agreement for the delinquents to have a better quality of life in the prisons,” Quijano said. “For them to have plasma screen TVs, for them to have open-ended conjugal visits . . . but where is the agreement to protect honorable citizens?” In short order, ARENA formally distanced itself from the truce, and the presidential candidate from the FMLN soon did the same. (Salvadoran law prevented Funes from running for a second consecutive term.)

Public opinion no doubt played a role in the parties’ reversals. One poll revealed that 83 percent of Salvadorans had a negative opinion of the truce, and 43 percent believed it had not reduced violence. This was partly a result of the sensational and critical media coverage, but it was true that the negotiators’ focus on the murder rate had led them to ignore other aspects of gang activity, such as gender-based and anti-LGBTQ violence. The truce had done nothing to address extortion, the practice that affected civilians most widely. (Castillo claims that they had begun discussing extortion with the gangs.) It was also true that gang leaders were enjoying plasma screens and conjugal visits in the prisons. Some had access to cable and internet, water heaters, and cell phones, and were allowed to host prostitutes and to throw parties behind the prison walls. A video of a so-called pornofiesta that went viral several years later showed strippers dancing naked in front of gang members at the Izalco prison in 2012.

The most serious blow to the truce, however, came when the Supreme Court decided to investigate the validity of Munguía Payés’s appointment as minister of public security. According to the Chapultepec Peace Accords of 1992, only civilians could hold the post, and Munguía Payés had commanded government forces during the war. In May 2013, the court ruled that it was unconstitutional for a military officer, even a retired one, to direct the ministry of public security or the national civil police. Munguía Payés, who had been responsible for enabling the mediators’ access to the prisons, was soon dismissed. Mijango called it an attempt to boycott the truce.

President Funes appointed Ricardo Perdomo as the new minister of public security. Perdomo, who had been involved in the truce as chief of the Office of State Intelligence, had never opposed the process, but Mijango didn’t trust him. On Perdomo’s first day in office, he held a staff meeting where he announced that “the party” was “over.” The mediators would no longer be allowed into the prisons. Journalists would be denied access as well. Before Perdomo took over, Nelson Rauda, the head of the National Prison Directorate, had arranged for two gang leaders to leave the prisons for a televised interview with the pastor of an evangelical church. The interview took place on the same day as Perdomo’s first staff meeting, and the next day, Rauda was fired. At a press conference, Perdomo announced investigations of the officials who had enabled the interview. He was accompanied by Martínez, the attorney general, and Mari Carmen Aponte, the American ambassador.

By January 2015, the truce was dead. The FMLN had won a close presidential election, and Salvador Sánchez Cerén, the new president, declared that the government would no longer negotiate with gangs. He sent the leaders back to Zacatecoluca. According to Mijango, the move was influenced by the Americans, who had just financed the construction of an even stricter new sector at Zacatraz, and wanted it put to use. That August, 907 homicides were committed, making it the most violent month of the century so far. The police intensified attacks on gang territory, forming special battalions, and were backed by more than seven thousand troops. Congress changed the legal code to make it harder to prosecute officers for killing in the line of duty. Reports surfaced of extrajudicial killings, and gangs responded by targeting police officers: in addition to the violence between the gangs themselves, a war between gangs and the state began. Overall, that year, the murder rate jumped by 70 percent, with 6,657 homicides committed. El Salvador became the murder capital of the world.

A few days after arriving in El Salvador, I visited a military base to speak to a high-ranking official involved in the truce. It was the brief but rainy winter season, and there was a pounding thunderstorm nearly every afternoon, but that morning it was sunny. The grounds of the base were a quiet green oasis from the traffic and noise of the capital. After being waved through one checkpoint and waiting in the car to pass through another, I watched soldiers stroll by, saluting their superiors, and it struck me how similar the experience was to entering a gang-controlled neighborhood—the checkpoints, the strict adherence to established codes, the chain of command. In one office, an M16 commemorating the war was encased in glass. The official told me there was in fact a gang-controlled neighborhood about a mile away from the base. I considered these two worlds, tightly ordered spheres of masculinity, so close together.

Before his involvement in the truce, the official had been a firm believer in Mano Dura, but that changed as he learned more about gangs. He said that they were a valve for social discontent, the same way the FMLN had been before it became a mainstream political party. Gangs had, in a way, replaced the guerrillas. “Who are the gangs?” he said. “The children of our bus drivers, workers, et cetera. And those were the people who the FMLN attracted.”

Mano Dura paralleled the military’s tactics in the years leading up to the war, when government forces targeted young men whose wardrobes imitated American fashion styles. My father, who had long hair and wore jeans, was arrested in the Seventies with a group of friends after someone falsely accused them of being guerrillas. The police blindfolded them and took them to a holding cell in San Salvador, where they were kept and questioned for days. When I told Castillo this story, he nodded and said, “A lot of us here became guerrillas not because we read Marx or Che Guevara. You know what my motivation was? When I was young, my dad came home beat up by the police.”

According to many people I spoke with, Salvadoran law enforcement tactics are now even more repressive than during the height of Mano Dura. In 2017, a UN representative investigated both the police and the prison system, and found rampant human rights violations. Police officers harass, and in some cases torture, civilians in gang-controlled areas, and they are feared just as much as gangs. The FMLN was, in effect, applying the same tactics that had been applied to its members throughout the civil war. “In the military, we did the same thing during the war,” the official told me. “We’re making the same mistakes.”

The official was convinced that dialogue was still the solution, and he had talked to many politicians who felt the same but couldn’t say so publicly. He also echoed the sentiment that the United States still viewed gangs principally as a security issue rather than a social one, which was ironic, he said, since the truce had been partly modeled on peace negotiations with gangs in Los Angeles. The current American ambassador, Jean Manes, has characterized the police repression as the actions of rogue officers and has voiced support for the same extraordinary prison measures that the UN representative had found to be in violation of human rights. Though the United States does fund some reinsertion programs, the bulk of recent US aid has gone to law enforcement and prison construction. For Salvadoran security officials, a different approach would carry the risk of losing hundreds of millions of dollars in support.

Mijango told me that the government has targeted him ever since the collapse of the truce. In 2014, Luis Martínez, the attorney general, accused Mijango of hiring someone to kill him, and then tried to connect Mijango to a kidnapping, though neither charge made it to court. In 2016, a new attorney general ordered Mijango arrested, along with Castillo and fourteen others involved in the truce, including psychologists, teachers, and prison wardens. The charges included organizing terrorists and introducing illicit objects into prisons. Mijango acknowledged that bringing food and cigarettes into Zacatecoluca was against the law, but, he pointed out, he was acting at the behest of the president and the minister of public security. He and the other defendants argued that they were being scapegoated for their participation in what had been essentially government policy. The judge seemed to agree. He dismissed the case and suggested the attorney general’s office investigate the “chain of command,” ostensibly pointing to Funes, the former president, who has since fled the country to avoid charges of corruption and was granted asylum in Nicaragua.

But Mijango’s legal woes didn’t end there. He was recently charged with homicide. The indictment centered on the phone call with Henríquez Solórzano, the MS-13 leader. Prosecutors interpreted “You all know what to do” as a directive to kill the gang member who had committed murder. The gang member was later assassinated in prison. Mijango’s case has yet to go to trial.

Mijango is now the only one of the truce’s core team of negotiators in prison, and he believes this is because he is the least powerful among them. Munguía Payés is the current minister of defense, and Colindres, the bishop, has the backing of the church. Mijango also has enemies across the political spectrum dating back to his break with the FMLN and, as the face of the truce, has been a target in the media. One recent headline read, “The Mutation of Raúl Mijango: From Guerrilla to Gang Member.” The day I met Mijango in the courtroom, when he was on trial for the extortion charges, the only person who had shown up to support him was Luers, his former guerrilla comrade. It had been a year since they’d last seen each other, and as they waited for Mijango’s co-defendants, imprisoned gang members who would participate virtually on plasma screens, the two old friends sat together chatting, as if they expected all of it to be over soon.

Alfredo Quijano, one of the prosecutors, told me that there are no legal protections for those who mediate negotiations with gangs in El Salvador. Mijango’s case was unprecedented. Quijano explained that by convincing gangs to lower the payment and modify its form, regardless of his intent and the company’s gratitude, Mijango was participating in extortion. It might’ve been a different story, Quijano added, if Mijango had convinced the gangs to stop extorting the company altogether, but the negotiation facilitated a continuation of the crime. Quijano also said that some of the company’s products had been found at a house owned by Mijango, which implied that he had benefited from the arrangement.

The fact that there was no legal strategy in place to protect the mediator of a government-backed truce was the product of the Salvadoran state’s reluctance to fully embrace the process, as well as the improvised manner of its execution. Some form of involvement in illegal activity or some degree of moral compromise was probably unavoidable in Mijango’s sprawling role as national gang whisperer. Professor José Miguel Cruz, a Salvadoran researcher at Florida International University who published a study of the truce, told me that this conundrum applies to anyone who cultivates close relationships with gangs, even with good intentions. “It’s very hard to establish a sort of clear line between . . . helping them to take the right steps . . . and helping them to continue with their criminal activities,” Cruz said.

But even the most skeptical Salvadoran journalists I spoke to, who readily question Mijango’s methods and point out his shortcomings, dispute the notion that he is corrupt. “I think that he entered the process because he believed in the process,” Óscar Martínez, one of the El Faro journalists who first broke the story of the truce, told me. “I don’t think he entered the process because the gangs gave him money or the government gave him a super salary. I think that later he did something braver. I think he continued with the process even while knowing that he was going to end up very screwed by this.”

On October 12, 2018, Mijango was convicted in the extortion case and sentenced to thirteen years and four months in prison. “They’re going to screw him,” a well-connected former judge had predicted to me. “This is something political.” The prosecution’s main witness was a gang member involved in the extortion who testified against Mijango under a plea bargain. The Salvadoran Supreme Court announced that the truce case, in which Mijango and others had been acquitted in 2017, would be retried. The homicide case is pending. As masked guards hauled Mijango out of the courtroom after the extortion verdict and reporters with microphones swarmed him, his easy smile was gone.

Mijango’s complicated legacy, however, will linger. The gangs have become more politically savvy, and the question of dialogue—of who has talked to gangs and who hasn’t—is now an essential one in Salvadoran politics. Nayib Bukele, who was elected president in February, was criticized for negotiating with gangs during his term as mayor of San Salvador and avoided the subject during his campaign. “Now you say . . . ‘dialogue with gangs’ and everyone thinks of the truce,” Martínez, the journalist, told me. “Now a politician who mentions it loses three points in the election. And when he does it again, he loses six.”

But Martínez pointed out that the government already negotiates with gangs in order to fulfill its most basic duties. It simply delegates that responsibility to its lowest rung of civil servants. In order to repair a broken pipe in a gang-controlled neighborhood, a water and sewerage employee has to ask the clica’s permission. A public-school teacher who wants children from the other side of the community to attend school has to talk to the gangs. Martínez believes that, because the truce was badly executed, it made the concept of dialogue politically impossible. For Salvadorans to be open to the possibility of dialogue again, Martínez said, the violence will have to spread beyond marginalized communities, until everyone, including the middle class and the decision-makers, is truly sick of it.

Popular desire for dialogue would depend upon accepting that the roughly sixty thousand gang members in the country, as well as the family networks who rely on them, are part of society and cannot all be imprisoned or killed. But most Salvadorans are far from ready to endorse a softer approach. For many, the idea of gangs as victims of repression is laughable. When I mentioned Mijango’s name, people would often insult him, sometimes profanely, for coddling gang members. One of my drivers in San Salvador, a former lawyer, told me that she had once been stopped and threatened by gang members because of the color of her hair; she had dyed it a shade of red that was reserved for their girlfriends. Her hair was darker now. When I asked her what should be done about gangs, her response was immediate. “All of them to the fire,” she said, “and let’s start from zero.”

La primera acusación, en el ‘caso tregua’, fue la más directa, y si se quiere, la más honesta: Acusaron la tregua como tal, y la política oficial del gobierno de facilitarla, permitiendo que vos y otros asumieran este papel de mediadores. Esta acusación fracasó, el juez determinó que la fiscalía trató de penalizar una política pública, y que los 19 acusados actuaron en el marco institucional de esta política. Por eso, desechó el caso.

La primera acusación, en el ‘caso tregua’, fue la más directa, y si se quiere, la más honesta: Acusaron la tregua como tal, y la política oficial del gobierno de facilitarla, permitiendo que vos y otros asumieran este papel de mediadores. Esta acusación fracasó, el juez determinó que la fiscalía trató de penalizar una política pública, y que los 19 acusados actuaron en el marco institucional de esta política. Por eso, desechó el caso.

Roberto Valencia, 29 agosto 2017 /

Roberto Valencia, 29 agosto 2017 /  gobierno) porque les estorba esta idea, porque desde el 2014 apuestan todo a la represión y la solución militar. Otros, porque destruyéndote a vos quieren llevarse de encuentro a Funes y Munguía Payés. Otros, porque quieren legitimar su triste historial de mano dura bajo los gobiernos de ARENA…

gobierno) porque les estorba esta idea, porque desde el 2014 apuestan todo a la represión y la solución militar. Otros, porque destruyéndote a vos quieren llevarse de encuentro a Funes y Munguía Payés. Otros, porque quieren legitimar su triste historial de mano dura bajo los gobiernos de ARENA…